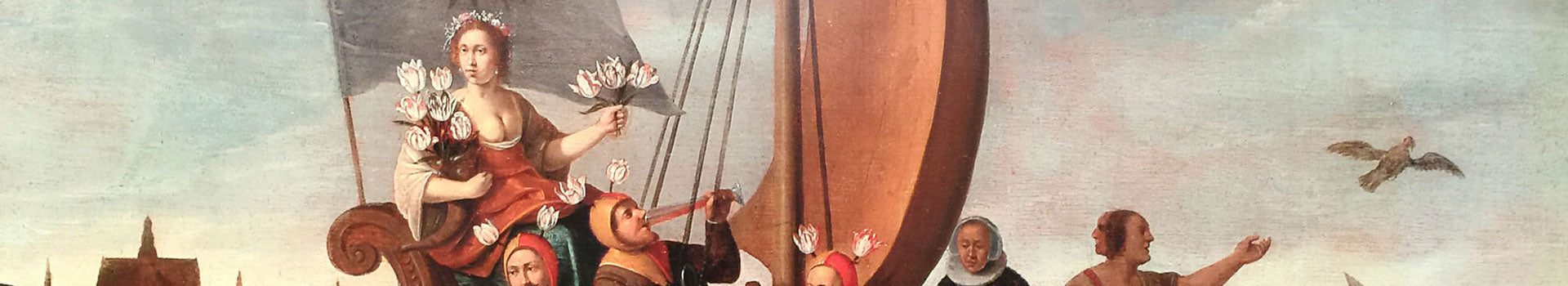

Holland and Tulipmania

The Dutch passion for tulips reached its zenith in the 17th century Holland.

Historical Backdrop

In the wake of a 1581 revolt against Spain, conflict drove many of Antwerp and Brussels’ merchants and artisans north to the newly founded Dutch Republic. At the same time, Protestant immigrants from other parts of the Spanish Empire streamed north, rapidly swelling the population of many Dutch towns to twice their size. Many of these immigrants had money to invest, a high work ethic, and substantial skill as craftsmen and artisans.

By the early 17th century, the Dutch Republic was one of the richest countries in Europe, with Amsterdam its most important city. This era saw the rapid establishment of the Dutch diamond industry and a stock exchange that funded the foundation of the wildly successful Dutch East India Company. The Dutch West India Company following only twenty years later.

The Tulip Boom

The growing Dutch population was packed into a small country where land for houses and gardens was at a premium. Property in Amsterdam was taxed by the width of its canal frontage. But the 17th century Dutch were also among the wealthiest people on earth. They were looking for ways to display their wealth, as well as to increase it. The tulip became the surprising vehicle for these ambitions.

At the time, the flower was still relatively rare. The tulip craze grew slowly, starting in the 16th century among a handful of late scholars and connoisseurs, who valued the “broken” tulip above all others. With time, the delicately striped and variegated broken tulips came to obsess people at all levels of Dutch society. Professional growers stepped in, followed by middlemen who often bought and sold bulbs without ever seeing them bloom. Often, no physical bulbs or tulips were actually sold, the trading instead occurred with a “futures contract"—a piece of paper guaranteeing the right to specific bulbs that would be blooming in the coming spring.

Finally, speculators, usually called florists, began to meet and do business in taverns all over the Dutch Republic. Many florists were middle class artisans, farmers and tradesmen. Some cared nothing for the flowers themselves, buying and selling the bulbs according to the model of the new futures markets established for Amsterdam grain sales. Florists simply wanted to get rich quickly. Their lively trade, fueled by tobacco and alcohol, drove prices up in a frenzied market boom.

By the mid-1630s almost anyone with money to spare seemed willing to risk it in the tulip market. Prices escalated exponentially. A single bulb sold one day for 46 guilders, then changed hands a month later for 515 guilders. Another bulb rose from 95 to 900 guilders in a similar period of time.

Tulipmania peaked in the early winter of 1637, with an auction at Alkmaar to benefit the orphans of the former local innkeeper and tulip speculator, Wouter Bartelmiesz. The previous year a single bulb of Semper Augustus, the most precious tulip of all, cost more than a sumptuous house on Amsterdam’s grandest Canal. The average price per bulb paid at Alkmaar (which did not include the most valuable tulips of the age) would have employed a master carpenter for two years, with the rarest commanding prices far higher.

Before the Alkmaar auction, the tulip market was already showing signs of strain. Then one day, at a tavern in Haarlem, a florist offered some bulbs at a reasonable price. There were no takers. He dropped the price a little, but still got no bidders. He cut his price again, to no avail. The crash had begun. Suddenly, across the republic, sellers far outnumbered buyers and the market began to collapse. In mid-February, the tulip trade was suspended and by June courts were refusing even to hear cases concerned with the fabulous flowers. The tulip fell into such disfavor that a prominent botanist was seen beating at the blossoms when he came upon them in Leiden, site of Carolus Clusius’ famous garden.

The botany of tulips supported the arc of boom and bust. The broken tulips that Dutch collectors and speculators so valued can’t be raised in large quantities from seed. Instead, they must be propagated by bulb division. This process builds healthy bulb stock exponentially, but yields only small increases for the diseased bulbs that produced Dutch treasures like Semper Augustus or Viceroy. Nonetheless, with time, even the rarest bulbs had become more common, a factor that also contributed to the crash in prices.