Holland After Tulipmania

After the dust of Tulipmania settled, the Dutch knew two things: they were good at growing tulips, and the mania in Holland had attracted worldwide attention. Curious European buyers created the demand for a new Dutch export market. These buyers were eager to see the beauties that had spurred Dutch collectors and speculators to insanity. But the export business really took off when a Turkish Sultan fell in love with tulips in the early 18th century.

A More Stable Flower Market Emerges

In the 1700s, Dutch bulbs supplemented the needle-petaled flowers the Turks grew themselves. Sultan Ahmet III regularly ordered thousands of bulbs from Dutch growers near Haarlem, where flower breeders also branched out into supplying the hyacinth bulbs that would fuel a separate mania. For most of the 18th century, the Dutch export trade was dominated by a handful of Haarlem growers.

As new farms were created by draining land near the sea, tulip growing shifted to the sandy clay soils of South and North Holland. The regions of Flevoland and the Noordoostpolder also began growing tulips, and today are known through postcard images of vast tulip beds.

By the late 19th century, the idea of planting dense beds of tulips as a landscape element had begun to take hold. The famous English gardener Gertrude Jekyll also favored mass plantings, but she wanted something more subtle. She began to blend two or more varieties in a single bed. Other influential gardeners favored the notion of allowing flowers to naturalize, creating the illusion of the fields strewn with tulips that, at their best, resembled the high flower-strewn fields of the steppes where tulips were first found the the wild.

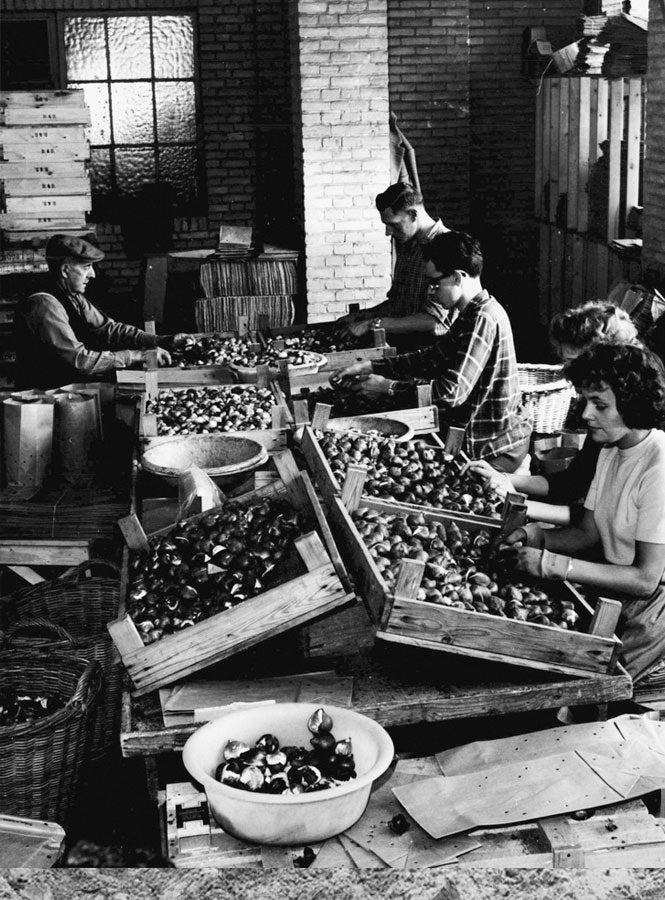

The Dutch grew tulip bulbs for all such schemes, turning their skill as horticulturists and salesmen to each new opportunity. As early as 1849, a grower sent a salesman to travel from New York to Washington to hawk bulbs all along his route. By the turn of the 20th century, Americans were buying more than a million dollars' worth of tulips each year.

In America and Europe, the Dutch learned to sell their flowers through beautiful catalogs, and by donating huge samples to public parks. With time, many people came to love tulips, and the flowers became much more affordable than they had ever been before.

Today, the Netherlands produces roughly 60 percent of tulip bulbs worldwide, even while agriculture and horticulture represent only a small share of Holland’s total economy.