Why Did Tulips Lead To An Economic Bubble In 17th Century Holland?

This Week's #TulipFact: Tulip Mania is widely regarded as the first "Economic Bubble", when the value of Tulips rocketed up, then almost overnight came crashing down. But bubbles don't just 'happen' - many factors came together to leave Holland ripe for such a craze!

This fact began when someone on Quora asked how Tulips gained their speculative prominence in the Netherlands, and we love Tulip Mania questions so were excited to answer. Before continuing, it is important to note that the economic and social factors that go into the creation of a 'bubble' like Tulip Mania are wildly complex, and the below is most certainly a simplification (and not the full story). And if you're curious, you can see the original Quora post and our response here.

So, diving in, why did a bubble occur? Why did Tulips reach a point of "speculation", where most buyers got involved not out of any interest in the flower itself, but with an expectation that the value would increase and they could then sell at a profit? Well, many different factors attributed to this, but some of the really key ingredients were:

- New wealth - The Dutch were hitting their Golden Age, where trade and mercantilism caused a massive bloom in wealth. That new wealth meant a rise in disposable income, and with that a desire to spend one’s money and 'show it off' a little bit.

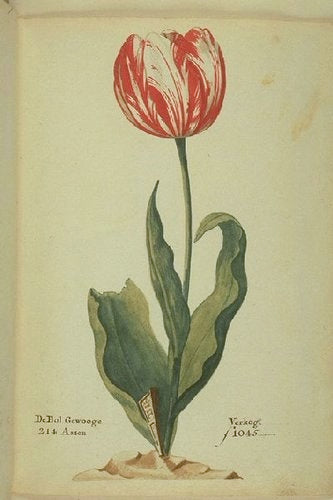

- Infatuation with rarities - Tulips were unlike anything that had existed in Holland before, and arrived a time when the Dutch were infatuated with owning and collecting 'curiosities' (quirks of nature such as the skeleton of a two-headed snake). Standing out against the grey landscape, the Dutch quickly realized that different flowers were what we would now call ‘genetically unique’. As a result, sellers played up the idea that every bulb was the ‘only one like this in the world’, which played into this current trend and helped drive a sense of rarity and value.

- Ease of trade (sometimes called 'liquidity') - This part gets fun - as the Dutch expanded their mercantile and financial prowess, they became experts in making trade and sales simpler and easier. Markets were everywhere, and so when the Dutch sought to begin trading bulbs, the 'infrastructure' of places to go and methods to auction and buy were already in place. Even more interesting, the height of Tulip Mania actually occurred when all of the bulbs were dormant underground (during the winter months of 1636–1637). Instead of letting the trade cease, the Dutch developed ‘Futures Contracts’ for the bulbs - easily traded pieces of paper that gave the bearer the rights to the bulb after it bloomed in the coming Spring. Changing hands many times a day, these contracts were extremely 'liquid' and made it easy to join to fray.

- Limited supply - Tulip bulbs take time and effort to reproduce. Bulb offshoots, where a mother bulb generates genetically identical 'bulbettes', typically require at least three years to reach flowering maturity. Tulips grown from seeds are even longer, at seven years. This left the supply of Tulips unable to keep up with rocketing demand, and was a key factor in early rising prices.

With these three ingredients, a picture of how the speculation occurred starts to become clear. Newly rich merchants would buy a bulb, which then spurred their friends to do the same. Prices would start to increase as supply was limited while more and more 'demand' entered the market for their own unique bulbs. Seeing an opportunity, some would then start selling their purchases for a profit. As the bulbs or contracts were easily traded, they could change hands multiple times a day.

Meanwhile, those watching from the sidelines would see fortunes being made as the value constantly increased. This would later result in speculators entering the market - as mentioned above, these were people who bought bulbs or contracts with no interest in the flowers themselves, only a desire to sell at a higher price. The presence of speculators is common in major economic bubbles - they bring in something of a 'fake demand', where every seller can find a buyer (often another speculator). This only increased the frenzy around the contracts. It is likely that, at its peak, many buyers were not doing so for the bulbs but simply to make a profit.

All of this came crashing down when buyers failed to show up at auction one day. It is unknown exactly why this occurred, although it is believed that to have been at least partially driven by 1.) Fears of plague and 2.) Concerns that the bulbs would soon be blooming, and therefore no longer trade-able. Regardless, the impact of this event is well known - anybody left holding a contract wanted to sell it as quickly as possible, and the bubble burst more or less overnight.

And so with that, Tulip Mania ended and the value of bulbs returned to reality. However, they seem to have won out in the end, as Tulips today remain loved around the world for their variety and magnificence :).

Image is of the satirical painting "The Tulip Trade" by an unknown Dutch artist. The meaning is obvious, where the painter portrayed the trade of bulbs as making a deal with the Devil (or alternatively, a trade of fools, depending on how one interprets the red & yellow outfit).